On the walls of the generous space were no fewer than seven large paintings in progress. Holmes had applied his characteristic earth tones to the Neo-Expressionist figures, which were just beginning to emerge. They were joined by a vanity license plate that reads THIBDAX (a truncated spelling of the artist’s Louisiana hometown, Thibodaux). Hanging above it were two paper mementos: a newspaper obituary for one young man and a funeral program for another. The two, Dantrell Anderson and Tyrone “T-Diddy” Anderson, were Holmes’s cousins, who had played formative roles in his life as a painter and father.

In 2016, with twenty dollars in his pocket borrowed from his mother, Holmes headed to Dallas, leaving the small Gulf town where he grew up. He had always drawn, and in 2019 he quit his day job to make art full time. His is something of a Cinderella story: in the past few years, his work has achieved sudden and rather extraordinary commercial success, thanks in no small part to celebrity collectors like Lenny Kravitz. Museums have barely begun to catch up. In a sense, his work lives in the liminal space between his hometown and his adopted city. Thibodaux is rural, and Holmes often describes the remnants of slavery visible in the town, which famously saw the tragic Reconstruction-era massacre of at least thirty-five Black sugarcane workers. He mines that history in his work, focusing on the everyday aspects of Black life in the Deep South. He’s always painting home, but from a distance.

Holmes opened up about his faith and spirituality; about the way his paintings, as outlets for trauma and emotions, have saved him; and about his mission to make this world a better place than he found it. Through the course of our hourlong conversation, the artist was disarmingly candid about everything—how and why he taught himself to paint, the legacy he sees in his sons, and the dark days that inform his paintings. Childhood trauma and anger put Holmes in a mental hospital when he was twelve. Eventually, he resorted to quietness and dissociation to deal with the unspoken hardship he sustained as a boy. But now, confronting his hurt and his hope—and often painting family members, early memories, or the sparrows he considers companions—Holmes finally feels liberated.

As we approached an imposing horizontal set of canvases on the center wall of Holmes’s studio, I saw birds in all the works in progress. Sparrows, to be exact.

CHRISTOPHER BLAY I’m drawn to these bird paintings—what are they about?

JAMMIE HOLMES Sparrows were always in my grandmother’s yard, all the time. And I never felt they were anywhere else. Everybody knew my grandmother—she was the candy lady and sold frozen cups [of Kool-Aid] and things like that. So walking up to her gate felt like walking up to a sanctuary. She always had these beautiful flowers and a nice yard, and everything else around was just, like, the streets. You know when you’re a kid, sometimes you’re lonely or depressed, and maybe you don’t know that you’re depressed, but you tend to fall in love with animals because you feel like they’re a part of you?

I was always looking at these birds, and I could never catch them. They were always gone before I could grab them. So birds and dogs were my thing. Being from the country, I never traveled. I never went anywhere. I was always thinking there was only home.

BLAY This is it, this block, this is everything!

HOLMES These sparrows only exist here! That’s what I was thinking, until I moved to Dallas. Now I know they’re all over the place! They got them in Detroit, Canada. . . . I wanted to carry that memory with me, and I wanted to give people that part of me. I wanted people to connect to the story of what the birds in the bushes meant to me. They meant freedom, because I felt like they followed me wherever I went. I felt like they were coming with me on my personal journey. They’re a symbol of home for me, they bring me peace. I wanted to give people a piece of me, so one day I came in and just started creating so many of them.

BLAY Are they individualized, or do you see them as . . .

HOLMES I see them as a group, as together. A lot of figurative art is, you know, people. I wanted to change it up a little bit and give viewers something totally different—a piece of my peace.

This painting with the buildings and the figures in front that I’m working on is of Narrow Street, the street I grew up on. This is my aunt’s mobile home, and there’s another mobile home in the back; my grandmother lived across the street from the mobile homes.

I just had a solo show at Library Street Collective in Detroit, and the people that really mattered to me were there—my mom, my brother, my cousins. It made me reminisce about home when I got back to Dallas. I was like, damn, I want people to realize that I grew up different, and I’m proud of it! I look at where I’m at now, and I’m like, Let’s remember the fact that I came from the country!

My little brother, who works in the studio with me running errands, saw the painting and was like, “Aw, man, I remember this, I remember that.” My cousin flew in to take care of some business out here, and when he came to the studio, he said the same thing.

This painting [in progress] is of the American Legion Hall where there were weddings and things like that. This one brings up so many memories.

BLAY Let’s get deeper into that, because it’s clear your work references memory a great deal. But memory can be unreliable. How are you playing with that malleability of memory in your paintings?

HOLMES When it comes to working from memories, I ask myself, “OK, what’s the heart of the painting? What’s going to give the painting the soul that I need to give it?” With House Party on Narrow Street [2020] and The Night After [2019]—Lenny Kravitz actually bought that second one—I was thinking about the house parties that my aunt had.

That place [in the unfinished painting] is iconic on our street. Back then, all you had to say was “I live near the American Legion Hall,” and it was like, OK! Me and my brother had a conversation earlier today, and I was like, man, if you didn’t play tackle or baseball, or get in a fight, or any of that in the Hall yard, youse not from Thibodaux! [Laughs.] Now we look back, and a lot of people didn’t make it this far with us. I look at my little boys, and when I was their age, we was in the streets already. Going through it when I was younger, it made me quiet.

BLAY You alluded to that earlier—talking about when kids are depressed, they get quiet.

HOLMES Yeah, I had got real quiet, and then I grew up and I wouldn’t talk to barely anybody. I was staying to myself because of all the stuff that I’d been through, and it wasn’t until painting that I was really able to regurgitate all of it. And now I notice that everything that I’m letting out makes me feel so much better. So I’m like, “Aw, hell yeah—the good, bad, ugly—y’all about to get this work!” [Laughs.]

I realized what separates me from anything that’s out there is how I grew up. I’m telling my story. There’s some things that I’ve been through in life that I know for a fact a lot of people didn’t. That was meant for me to have, and meant for me to deal with.

BLAY Talk to me about that.

HOLMES I’ma just say it like this: I feel like I was cheated out of being a kid. And that’s all I can say about that.

This mornin’ I told my sons, “For a moment, I thought I was teaching you guys, but in reality I’m learning from you. Everything I am is already in the both of you. I’m learning how to control the things that’s in me through you.” I get to sit back and watch how they control everything that I’ve given them. They was born me. My temper, they inherited that. But I get to see them laughing when they get upset. I’m like, how in the hell?! I’d be blowin’ my top!

Another time I was laying in bed at night and I heard them laughing, versus when I was a kid and I used to hear my stepdad abusing my mom, or they would be arguing . . . I used to hear that shit when I was in bed. Now I get to hear something different and it’s flooding all that bad shit out. I used to be so angry. I would go to therapy, and I felt like even therapy didn’t get at it. But now, everything that I’m getting from my kids is showing me different. Like the laughter, them joking around.

BLAY That’s got to be a beautiful feeling, man. Both a break from and a connection to the past.

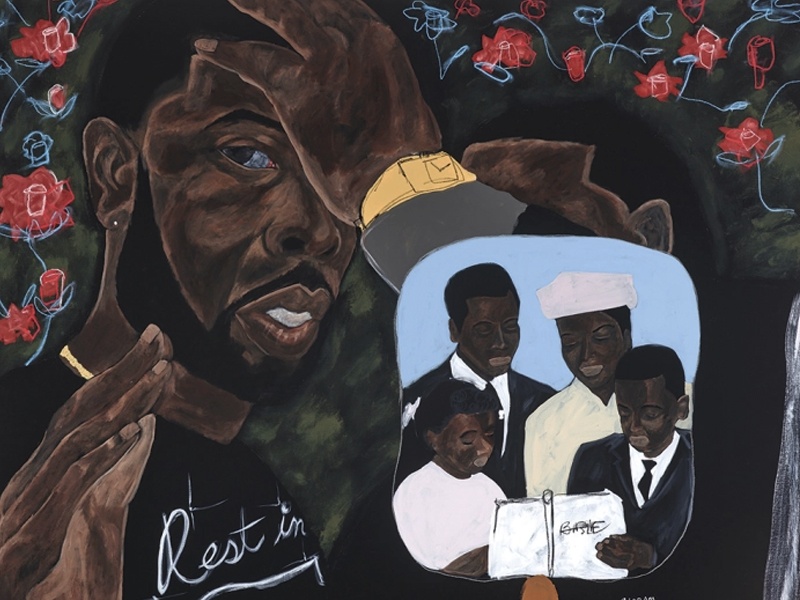

HOLMES My older cousin Tyrone, who I really clung to, died in a car accident in ’09. That was another reason I got quiet again. Dantrell, my other cousin, was murdered in ’06. Them two were brothers, and I was more connected with Tyrone—he was like a father figure to me. Dantrell, he gave me so much courage. I was like, “Nobody’s gonna fuck with me, I’m related to Dantrell!” He gave everybody that confidence.

Tyrone was the one that said, “Oh, man, draw me a picture of Bob Marley!” I was probably twelve years old, but I knew how to draw people real good at a young age. Man, he would give me a hundred bucks! I was selling sketches early on in my life. To this day, my grandma still got my sketches in frames from the dollar store. Some are still hung up in the same exact spot where they’ve been since I was a child.

BLAY When you look back at stuff like that, can you draw a line from that experience to this painting of the Hall yard on the wall right now? These are large canvases with a lot of detail of your neighborhood and the people you saw every day. I mean, as a kid doing sketches, could you see it becoming what it is today?

HOLMES Yes. I was able to sketch anything that was in front of me. When I was younger, my cousin would give me all these assignments. I sketched Marcus Garvey for ’em. They pushed me. They was like, “Man, you got million-dollar hands!” Nobody who’s from the country, or from the hood, knew nothing about the art world.

BLAY So how did you go from that point to, let’s say, your first art exhibition? Walk me through that point where you said, “OK, I’m gonna get in this hustle, I’m gonna do this thing.”

HOLMES I stopped sketching. I ripped all that shit off my wall and threw it away. My mom always tried to encourage me. She didn’t understand me at all, but she would buy me art supplies every Christmas. I was a grown-ass man working in the oil fields, but she still bought me art supplies. She just knew I liked sketching when I was a kid, so she kept the dream alive, I guess.

When I moved out here, I went to the KAWS exhibition at the Modern [Art Museum of Fort Worth], and when I walked in there, I was like, man! I could do that. [Big laugh.]

And then I realized how hard it really was. Man, where do you even buy paint from? I was using all the wrong shit, and I was making some trash. Then it got to a point where I stopped doing it, because I realized I was trying to do something based off of competing versus a raw emotion. Then I went to New York [in 2016]. I started painting again; I was painting genuine, and it started feeling good. It was real abstract, but I still had figures in the work. Somebody had said, “Oh, it reminds me of Basquiat.” I didn’t want to look like I was ignorant, so I said, “Oh, yes, thanks!” I swear, if I’m lyin’, I’m dyin’, but I did not know who Basquiat was. I never saw his work!

I didn’t know anything about art at this time; [my work] was me, genuinely, just me regurgitating my anger, just me speaking to myself. Mind you, you’re looking at a person that brushed his teeth without looking directly in his own eyes for a long time. It wasn’t until my [2021] solo show when I really painted myself [Blame the Man] and decided that I was going to face myself for the first time and be as normal as I can. I was like, I didn’t even know I looked like this, what the fuck! I was super excited.

BLAY Do you feel like you were so introverted that you could hardly even look at yourself in the mirror?

HOLMES I was so upset at the things I allowed myself to go through when I was younger. I know I didn’t have control over it, but I hated it. It made me sour, bitter, angry. I couldn’t look myself in the eye and admit that I was hurt. I didn’t know how. I didn’t tell my mom, I didn’t tell nobody. It was like, damn, man, this is a horrible life. I would rather just kill myself at this point. But I was able to help myself through art—just pouring it out and pouring it out.

That’s where the Basquiat comparison came from. I was like, Let me just find out who this dude is. But I didn’t find out on Google. I flew to New York. I went to his grave. I wanted to see if I could feel something, to pay homage. I’m a real spiritual person.

BLAY That’s that Louisiana shit too, though!

HOLMES Yes! [Laughs.] But I was at the graveyard and said, Let me try to talk to Basquiat. I was like, “Man, I’m not trying to step on your toes. I’m just painting my truth.” And then I felt at peace with the comparison, and I left.

I started painting right after that [in 2016], and I haven’t been able to hold on to a painting since then. They’re all sold—just gone, gone, gone. I felt that this was people feeling my truth. They saw me being sincere in what I’m doing. I wasn’t trying to be like nobody. I wasn’t acting. I was just painting my truth.

If you go back, you can see that I was just developing. I had some paintings with figures, and you can see that I didn’t know how to paint faces. But I wanted to, so I didn’t even care! I was putting that essence of how I felt about certain things into the work, and then it started growing. I decided to do faces in oil pastels. Then I felt like, Oh! I know what I’m doing—I’ve been drawing faces basically my whole life! I didn’t start painting faces until late 2019.

BLAY OK, so in the painting Uncle [2019], for example, there’s a figure without a face. This was before you started painting faces?

HOLMES Yeah. I didn’t know how to paint faces, but I wanted to paint the essence of this man who was beat up by America. My uncle lived this long life; he went to prison for a long time.

I paint because I love what I do. And I let the gallery [Library Street Collective] choose what they want, and that’s fine. But some shit I can’t let go of. When I did Uncle, it was like, man, I just wanted to get that out of me, because I was thinking about it, you know?

BLAY I noticed that some of the figures in Second Childhood [2020] also don’t have faces.

HOLMES With Second Childhood . . . I always say Thibodaux is full of adults who grew up too fast, because, man, we had no choice! It was adapt or die! We had to walk to school, and you don’t know what’s about to happen on your way. We saw cars crash, guns waved, shootings, drugs, prostitutes, fistfights, everything. And growing up, it was hard to express yourself. You didn’t want to look soft. You couldn’t go out and be like, I’m actually sad, I feel like X, Y, Z. So everybody just turns to anger.

Mine was so bad that I was in a mental institution when I was my kids’ age. While everybody was enjoying summer, I was in the Bayou Oaks mental institution. Nobody knew. How are you supposed to tell them, I’m sad? They’d say, “You ain’t sad, shut the hell up and go eat your dinner.”

BLAY Yeah. It’s like Black folks can’t get depressed!

HOLMES No. [Our parents] was going through a different type of time. I’ve always told my friends, man, never fault our parents from that era. Now, this era? You got a problem!

BLAY Right, because we know better! Another thing I noticed about your paintings is their limited palette. I wonder if restricting your palette is just saying more with the tools you have, or . . .

HOLMES That’s it. And I’m glad you said that. Ask anybody that really knows me—I work with a limited palette because I don’t complain. If I ain’t got no tubes of paint, and I have a puddle of paint on the ground,

I’m using that puddle.

BLAY There are some recurring motifs in your paintings that I picked up on too. One of them is the black and-white checkered floor.

HOLMES The checkered floor reminds me of back in the day when my aunts had checkered floors in their homes. At the same time, I used the checkered floor for the yin and the yang of a person. Everybody has a

good side and a bad side, you know what I mean?

Then I saw in my research that [checkered floors are] in the South, in Africa, and all over the place. It’s amazing, like, damn, man, that’s how connected Blacks really are even though we don’t have the

same situations.

BLAY Your public work titled They Are Going to Kill Me [2020] was a profound gesture—you transformed some of George Floyd’s last words into banners that were flown over five different cities across the country. Airspace can be a threatening space for Black people to occupy, especially because it’s used by governments for surveillance, intimidation, or to rain down destruction. How are you using this to speak to that language of violence that you see in the policing of Black bodies?

HOLMES The aerial demonstration was a peace-type moment, a moment almost like, “You know what? Man, you don’t understand how tired we are.” I’m not about to go out there holding signs, man. My family did that shit. I’m doing something different. I’m tired.

That’s what the [embroidered] flag [I’ve Seen It All, 2020] was about. It was for Black folks to hold hands and say together, “Hey, see it the way we saw it through our skin.” That’s why the eyes are on the black part [of the flag], to say, “See it the way we had to see it.” Instead of being pissed off and chopping you down because we’ve got history, it’s for us to tell you, “Dude, have some understanding, have some compassion,

and then let’s go from there.”

BLAY Man, that’s heavy. It’s a burden, a responsibility, and an obligation. I feel like it’s all those things wrapped into one.

HOLMES My little brother had just moved out here to come work at my studio, and I was so proud of him. Man, so many people are afraid to leave Thibodaux. When I came out here, I had nothing. But when he came, I got him his apartment, I gave him a car, a job, everything. I’m his big brother. This sparrow painting I’m working on right now is based off the fact that he had the courage to leave that city. He’s bringing his sparrows with him and he’s going to flourish and do his thing. He’s free.

BLAY Tell me more about your spirituality.

HOLMES I didn’t really believe in God until about 2018. So it’s new, and I’m like, “Oooooh!” I’m so excited about it! I know my journey is to educate in a poetic way, because my work to me is poetry more than painting.

BLAY Do you title your paintings after you create them?

HOLMES Oh, yes. Or during, if I hear something. I sense that people probably think I’m crazy because

I say I hear, literally, with my eyes. I’ll turn off all the music, and I’ll just sit with my painting, because once the work is gone, it’s gone.

BLAY You’re painting home. It must be hard to let home walk out of the studio.

HOLMES Exactly. Next year I’m probably gonna implement interviews with anybody that’s buying my work. I don’t care how much money you spend. If you want this piece that bad, you give me ten minutes of your time. That’ll help me let go of my work more easily. And also, I want to explain it to you.

BLAY You mean you want your paintings to go to someone who’s genuinely moved by the work,

not someone who’s just looking for who’s hot right now? Like somebody saying, “Gimme six of those.”

HOLMES Yes, exactly. Talk to me—give me some of your time. Shit, I’m giving you my life! Give me ten freaking minutes. To be honest, if all this stops today and nobody buys one more piece, I’m still going to be in here doing what I got to do, because this has helped me become a better person for them two. [Gestures toward the room where his children are.] I put them in this world. They didn’t ask to be here; I owe them everything.

This interview was originally published in ArtNews