Michael Lobel on Romare Bearden in the 1930s

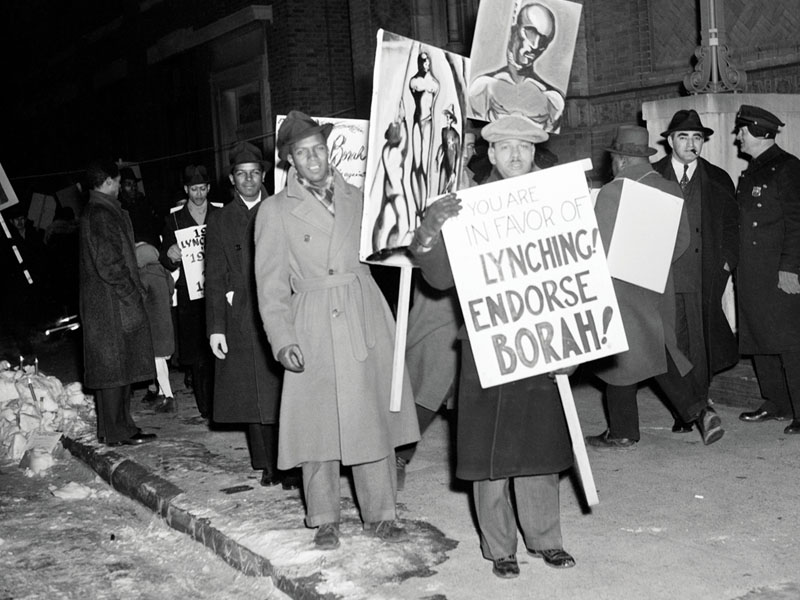

SO AS NOT TO BURY THE LEDE, as the old journalistic saying goes, I’ll make things perfectly clear right from the outset: It’s very likely that this 1936 black-and-white photo of a protest in Brooklyn captures two hitherto unknown paintings by Romare Bearden, one of the twentieth century’s most celebrated African American artists. If that’s the case, these would be among the earliest, if not the earliest, painted works by Bearden on record. And, in their depiction of lynchings, they would help illuminate an important yet little discussed period in the artist’s career, when he created intensely political imagery that continues to speak to the urgent concerns of our own day.

In the 1930s, Bearden was not yet an accomplished collagist of scenes of Black life and experience, the kinds of pictures for which he has become best known. He had not yet arrived at the New Testament imagery he would produce in the ’40s, nor had he begun his experiments with abstraction, a move he would make alongside so many other artists at midcentury. In fact, in the ’30s, Bearden hadn’t yet claimed the mantle of fine artist at all; rather, his primary calling was cartooning, a pursuit he threw himself into with drive and dedication. Throughout much of that decade, he contributed illustrations to a wide range of periodicals: campus publications during his student years at Boston University and New York University; mass-market magazines targeted primarily at middle-class white audiences, like Collier’s, The Chicagoan, and Judge; the Baltimore-based Afro-American, an influential Black-owned newspaper; and the publications of political organizations, such as the National Urban League’s Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life and the NAACP’s The Crisis.1 In this engagement with a journalistic milieu, he was following in the footsteps of his mother, Bessye, a major figure in Harlem’s civic life and a New York correspondent for the Chicago Defender. We can even trace Bearden’s use of collage techniques back to this period, since in several instances he cut and pasted newspaper fragments into panels, not for the purposes of formal experimentation but to offer political takes on newsworthy events.

It’s exceedingly common for artists’ output in popular, ephemeral contexts to be taken less seriously than their endeavors in more traditional artistic media. In this case, that needs to change.

Bearden’s longest-running efforts as a cartoonist were the weekly panels he produced, over the course of a year and a half, for the Afro-American, where his subjects ranged from Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia to the integration of American institutions of higher education to the GOP’s failed promises to Black voters. His very first outing for the paper tackled the recent legislative record on lynching. It showed an anthropomorphic bill (a precursor to the title character of the famed “I’m Just a Bill” segment of the ’70s Saturday-morning-cartoon staple Schoolhouse Rock!) sitting isolated and forlorn atop a featureless outcropping.2 A label identifies it as the Costigan-Wagner Bill, one of a number of pieces of anti-lynching legislation that were repeatedly blocked in that era, at times through Senate filibuster—circumstances that ring sadly familiar today. When one of the most vocal opponents of that legislation, Idaho senator William E. Borah, threw his hat in the ring for the Republican presidential nomination, he was soon met with opposition organized by the NAACP and other groups. Which helps explain the circumstances of the photo with which I began.

On that bitterly cold night in late January—so frigid that ice floes on the Hudson were impeding traffic in New York Harbor—demonstrators braved below-freezing temperatures to protest a speech Borah was delivering in a Brooklyn auditorium. The myriad details captured in the photograph help set the scene: picketers assembled in front of the venue, bundled up against the cold; snow piled along the curb; a police detective right out of central casting, complete with fedora and cigar stub jammed into his mouth, glaring at us from the background. And at center, behind a sign that pointedly makes the case against Borah, protesters brandish two painted depictions of lynchings. (A third such image is visible, just barely, in the left background.) In that period, artists had been addressing the subject with some regularity, particularly in the many entries to two anti-lynching art exhibitions mounted in New York the previous year.

From the Afro-American, February 8, 1936.

Numerous articles covering the Brooklyn event in the Black press explained that the protest placards were supplied in part by Bearden—who was identified as a “well known young cartoonist”—and Aaron Douglas, the painter and illustrator responsible for some of the defining imagery of Harlem Renaissance art. There are several reasons why Bearden is the most plausible creator of those two foreground images. For one, they aren’t consistent with Douglas’s signature silhouetted style of the time, as seen in murals he painted not long before for the New York Public Library’s 135th Street branch in Harlem. Moreover, the text of a partially obscured sign accords with what various news reports suggested was Douglas’s sole contribution to the event.3 Finally, aspects of the painted placards in the photo align with known imagery by Bearden. For instance, the rendering of the figure in close-up, head-and-shoulders view is similar to that in one of his best-known early paintings, The Visitation, 1941, at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Given all the above, and considering that the press accounts identify no other artists by name, it’s extremely likely these were Bearden’s handiwork.

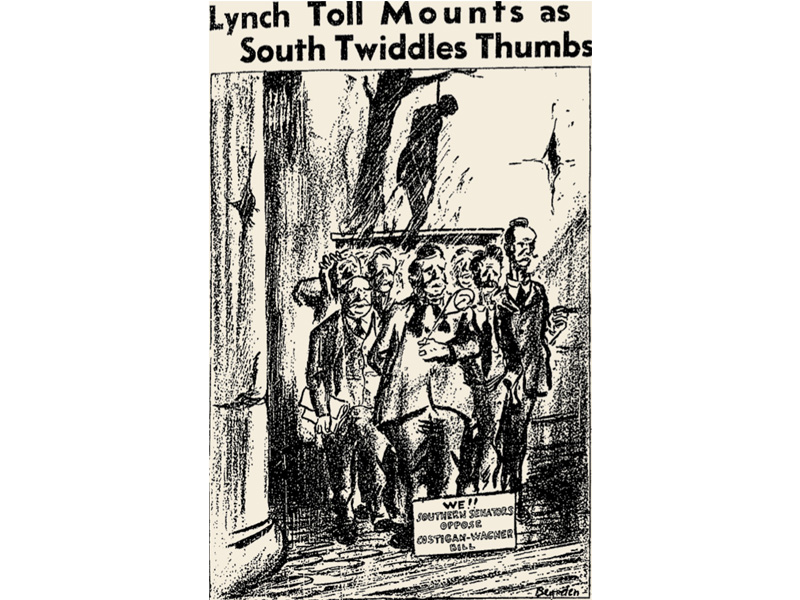

From the Afro-American, November 23, 1935.

On more than one occasion, Bearden used his cartooning to castigate politicians who opposed anti-lynching legislation, including in a disquieting front-page Afro-American illustration that posed a gaggle of Southern senators beneath the figure of a Black man hanged from a tree. The Ku Klux Klan was another frequent target. Bearden took pains to convey the terror the group sowed, as in one panel for The Crisis that linked the Klan’s activities to Nazi campaigns of persecution in Germany. In some instances, however, including a number of his efforts for the Afro-American, Bearden seems to have shifted tone, as he presents the Klan in a satirical, mocking, even absurd light. While still engaged in malign doings, they come off as clownish. In one panel, a Klansman balances precariously on a rickety ladder, paintbrush in hand, a literalized symbol of whitewashing. In another, which comments on segregation in the Methodist Episcopal Church, a hooded Klansman perches cross-legged on a church steeple, set impossibly high in the air like an ungainly bird atop a pole.

From the Afro-American, April 11, 1936.

I’ve come to view these drawings by Bearden as unacknowledged precursors to Philip Guston’s so-called hoods, the subject of contentious art-world discussion in recent years. Although Guston had tried his hand at a few pictures of hooded conspirators in the ’30s, his signature ham-fisted portrayals of such figures didn’t come until decades later. Even though there is a great deal that connects these two artists, who were born less than two years apart—early engagements with political art, subsequent moves into abstraction, later returns to figuration—Bearden has been absent from recent debates about the exhibition of Guston’s Klan imagery. If that’s due in part to the conventionally racialized framing of artistic influences and lineages, it is also because Bearden’s substantive work in cartooning has remained largely unknown or overlooked. It’s exceedingly common for artists’ output in popular, ephemeral contexts—cartooning, illustrating, advertising, and the like—to be taken less seriously than their endeavors in more traditional artistic media. In this case, that needs to change, and Bearden’s images should be kept in mind as the conversation about Guston continues to play out.

Let’s return, one last time, to that 1936 photo of the protest in Brooklyn. Zooming in, we catch sight of a telling detail. Along the edge of one of the painted placards, we can make out what look to be tacks or nailheads, suggesting that this is the tacking edge of a painter’s canvas. If that is indeed the case, then it appears that a wooden handle was affixed to the painting to turn it into a protest sign—as condensed an emblem of the subsumption of art into politics as one could imagine. It suggests that whoever created the placard found themselves repurposing the tools of easel painting for the express aims of political activism. That simple, makeshift assembly offers the kind of historical precedent I know many have been looking for of late, yet another in a long line of examples of artists taking their work out of the studio and sending it into the streets.

Michael Lobel is a Professor of Art History at Hunter College and the Graduate Center, CUNY.

My deepest thanks to curators Ruth Fine and Tracy Fitzpatrick for sharing their expansive knowledge of Romare Bearden and his work with me.

NOTES

1. The most extensive accounting of Bearden’s 1930s cartooning has been provided by scholar Amy Helene Kirschke, as in her essay “Bearden in The Crisis: Illustrating Identity and Political Action,” in Romare Bearden, American Modernist, ed. Ruth Fine and Jacqueline Francis (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2011), 101–17.

2. Romare Bearden, Found—The Forgotten Man, Afro-American, September 28, 1935, 6.

3. “The placards designed by Mr. Douglas showed a Negro being lynched, with the legend ‘Borah Opposes a Federal Law to Stop This.’” “Pickets at Borah Meeting,” The Crisis, March 1936, 88.

This article was originally written by Michael Lobel for ArtForum